Outcome harvesting

Outcome Harvesting collects (“harvests”) evidence of what has changed (“outcomes”) and, then, working backwards, determines whether and how an intervention has contributed to these changes.

Outcome Harvesting has proven to be especially useful in complex situations when it is not possible to define concretely most of what an intervention aims to achieve, or even, what specific actions will be taken over a multi-year period.

1 What is Outcome Harvesting?

Outcome Harvesting is an evaluation approach in which evaluators, grant makers, and/or programme managers and staff identify, formulate, verify, analyse and interpret ‘outcomes’ in programming contexts where relations of cause and effect are not fully understood.

Outcomes are defined as changes in the “behaviour writ large” (such as actions, relationships, policies, practices) of one or more social actors influenced by an intervention. For example, a religious leader making a proclamation that is unprecedented and considered to be important; a change in the behaviour between organisations or between communities; changes in regulations, formal laws or cultural norms.

Unlike some evaluation approaches, Outcome Harvesting does not measure progress towards predetermined objectives or outcomes, but rather, collects evidence of what has changed and, then, working backwards, determines whether and how an intervention contributed to these changes. The outcome(s) can be positive or negative, intended or unintended, direct or indirect, but the connection between the intervention and the outcomes should be plausible.

Information is collected or “harvested” using a range of methods to yield evidence-based answers to useful, actionable questions (“harvesting questions”).

Outcome Harvesting can be used for monitoring as well as for evaluation (including developmental, formative or summative evaluation) of interventions or organisations.

2 Where does Outcome Harvesting come from?

The approach is inspired by Outcome Mapping and informed by Utilisation-Focused Evaluation. It was developed by Ricardo Wilson-Grau and colleagues* who, as co-evaluators, applied it in different circumstances and further refined it over many years of evaluation practice.

*Barbara Klugman, Claudia Fontes, David Wilson-Sánchez, Fe Briones Garcia,Gabriela Sánchez, Goele Scheers, Heather Britt, Jennifer Vincent, Julie Lafreniere, Juliette Majot, Marcie Mersky, Martha Nuñez, Mary Jane Real, NataliaOrtiz, and Wolfgang Richert.

3 When can Outcome Harvesting be used?

Outcome Harvesting is particularly useful when outcomes, and even, inputs, activities and outputs, are not sufficiently specific or measurable at the time of planning an intervention. Thus, Outcome Harvesting is well-suited for evaluation in dynamic, uncertain (i.e., complex) situations.

Outcome Harvesting is recommended when:

- The focus is primarily on outcomes rather than activities. Outcome Harvesting is designed for situations where decision-makers (as “harvest users”) are most interested in learning about what was achieved and how. In other words, there is an emphasis on effectiveness rather than efficiency or performance. The approach is also a good fit when the aim is to understand the process of change and how each outcome contributes to this change.

- The programming context is complex. Outcome Harvesting is suitable for programming contexts where relations of cause and effect are not fully understood. Conventional monitoring and evaluation aimed at determining results compares planned outcomes with what is actually achieved, and planned activities with what was actually done. In complex environments, however, objectives and the paths to achieve them are largely unpredictable and predefined objectives and theories of change must be modified over time to respond to changes in the context. Outcome Harvesting is particularly appropriate in these more dynamic and uncertain environments in which unintended outcomes dominate, including negative ones. Consequently, Outcome Harvesting is particularly suitable to assess social change interventions or innovation and development work.

- The purpose is evaluation. Outcome Harvesting can serve to track the changes in behaviour of social actors influenced by an intervention. However, it is designed to go beyond this and support learning about those achievements. Thus, Outcome Harvesting is particularly useful for on-going developmental, mid-term formative, and end-of-term summative evaluations. It can be used by itself or in combination with other approaches.

The timing of “the harvest” depends on how essential the harvest findings are to ensure the intervention is heading in the right direction. If the certainty is relatively great that doing A will result in B, the harvest can be timed to coincide with when the results are expected. Conversely, if much uncertainty exists about the results that the intervention will achieve, the harvest should be scheduled as soon as possible to determine the outcomes that are actually being achieved.

4 Who should be involved in Outcome Harvesting?

A highly participatory process is a necessity for a successful Outcome Harvesting process and product.

Depending on the situation, either an external or internal person (“the harvester”) is designated to lead the Outcome Harvesting process. Harvesters facilitate and support appropriate participation and ensure that the data are credible, the criteria and standards to analyse the evidence are rigorous, and, the methods of synthesis and interpretation are solid.

“Harvest users” are individuals or organisations requiring the findings to make decisions or take action. They should be engaged throughout the process. These users must be involved in making decisions about the design and re-design of the approach as both the process and the outcomes unfold. Also, the principal uses for the harvest may shift as findings are generated which, in turn, may require re-design decisions.

The harvester also needs to engage informants who are knowledgeable about what the intervention has achieved and how, and who are willing to share, for the record, what they know. Field staff who are positioned “closest to the action” tend to be the best informants.

5 How is Outcome Harvesting done (overview)?

The harvester obtains information from the individual(s) or organisation(s) implementing the intervention whose actions aim to influence outcome(s) in order to identify actual changes in the social actors and how the intervention influenced them.

“Outcome descriptions” are drafted to a level of detail considered useful for answering the harvesting questions. The descriptions may be as brief as a single sentence or as detailed as a page or more of text. They may include explanations of context, collaboration with or contributions from others to the specific outcome; diverse perspectives on the outcome; and, the importance of the outcome. The harvested information undergoes several rounds of revisions to make it specific and comprehensive enough to be verifiable.

Subsequently, the information about select outcomes is validated by comparing it with information collected from other knowledgeable and authoritative, but independent, sources.

Finally, the validated outcome descriptions are analysed and interpreted –either as an individual outcome or as a group of outcomes– for their significance in achieving a mission, goal or strategy and are used to answer the harvesting questions.

6 How is Outcome Harvesting done (six key steps)?

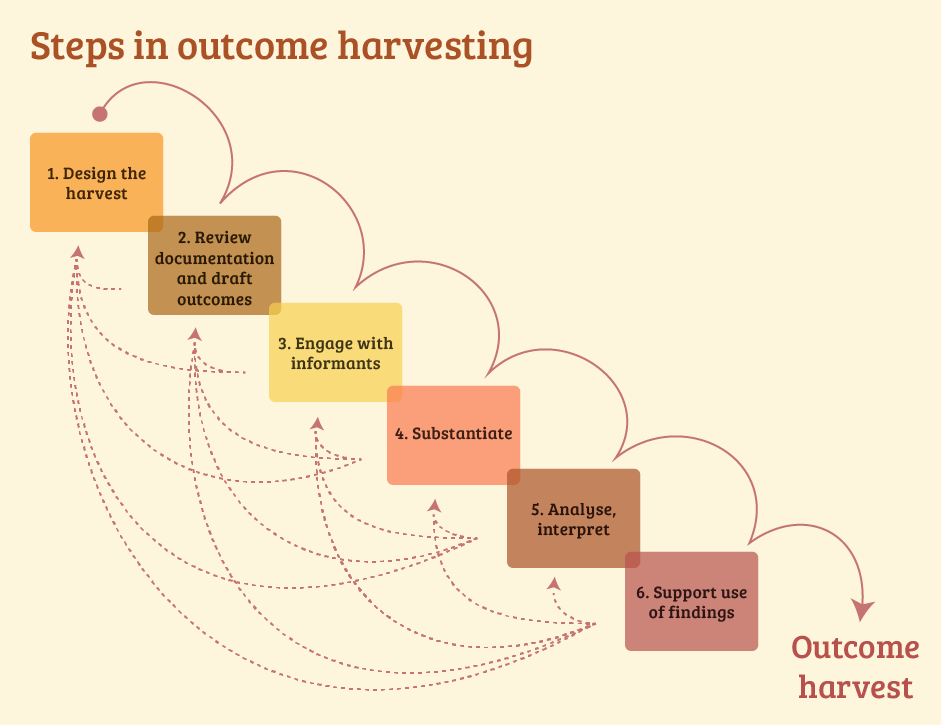

The Outcome Harvesting approach should be customised to the specific needs of the primary intended users/uses. The six “steps”, discussed below, are to be taken more as guiding principles rather than rigid formulae to follow. Nonetheless, the rigorous application of all six principles is necessary for a sound and credible outcome harvest.

-

Design the Outcome Harvest: The first step is to identify the primary intended users of the harvest and their principal intended uses for the harvest process and findings. Based on those, the harvest users and harvesters agree what needs to be known and write useful, actionable questions to guide the harvest (harvesting questions). For example, a useful question may be: What has been the collective effect of grantees on making the national governance regime more democratic and what does it mean for the portfolio´s strategy? Then, they agree what information is to be collected and from whom in order to answer the questions. At a minimum, this involves obtaining information about the changes in social actors and how the intervention influenced them.

-

Review documentation and draft outcome descriptions: From reports, previous evaluations, press releases and other documentation, harvesters identify potential outcomes (i.e., changes in individuals, groups, communities, organisations or institutions) and what the intervention did to contribute to them. For example, the change can be a president’s public commitment to being transparent (behaviour); two government agencies collaborating rather than competing (relationships); a minister firing a corrupt civil servant (action); the legislature passing a new anti-corruption law (policy); or a third successive government publishing its procurement records (practice). The influence of the change agent can range from inspiring and encouraging, facilitating and supporting, to persuading or pressuring the social actor to change.

-

Engage with informants in formulating outcome descriptions: Harvesters engage directly with informants to review the outcome descriptions based on the document review, and to identify and formulate additional outcomes. Informants will often consult with others inside or outside their organisation knowledgeable about outcomes to which they have contributed.

-

Substantiate: Harvest users and harvesters review the final outcomes and select those to be verified in order to increase the accuracy and credibility of the findings. The harvesters obtain the views of one or more individuals who are independent of the intervention (third party) but knowledgeable about one or more of the outcomes and the change agent’s contribution.

-

Analyse and interpret: Harvesters, classify all outcomes, often in consultation with the informants. The classifications are usually derived from the useful questions; they may also be related to the objectives and strategies of either the implementer of the intervention or other stakeholders, such as donors. For large, multidimensional harvests, a database is required to store and analyse the outcome descriptions. Harvesters interpret the information and provide evidence-based answers to the harvesting questions.

-

Support use of findings: Harvesters propose issues for discussion to harvest users grounded in the evidence-based answers to the harvesting questions. They facilitate discussions with users, which may include how they can make use of the findings.

These steps are not necessarily distinct; they may overlap and can be iterative; feedback can spark decisions to re-design a next step or return to or modify an earlier step. Typically, feedback from step 4 (substantiation) and step 5 (analysis and interpretation) does not influence the earlier steps; feedback from step 6 (support of use) only affects step 5 (analysis and interpretation). Nonetheless, feedback from all the steps can, of course, influence decisions about future harvesting for either monitoring or evaluation purposes.

It should be noted that “Outcome Harvesting” is done as often as necessary to understand what the change agent is achieving. Depending on the time period covered and the number of outcomes involved, the approach can require a substantial time commitment from informants. To reduce the burden of time on informants, outcomes may be harvested monthly, quarterly, biannually, or annually. Findings may be substantiated, analysed or interpreted less frequently.

The above steps are explained in more detail in Outcome Harvesting by Wilson-Grau R and Britt H (2013).

7 Where and by whom has Outcome Harvesting been used?

Nongovernmental organisations, community-based organisations, networks, government agencies, funding agencies, universities and research institutes have used Outcome Harvesting in over 143 countries. In 2013, the Evaluation Office of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) selected Outcome Harvesting as one of eleven promising innovations in monitoring and evaluation practice. After ten teams of the World Bank Institute piloted a customised version of the Outcome Harvesting, the approach and tools as customised for the Institute were listed amongst its resources for internal monitoring and evaluation. The US Agency for International Development (USAID) chose Outcome Harvesting as one of five approaches particularly suited for monitoring and evaluation in dynamic, uncertain situations.

Thus, Outcome Harvesting has proven to be a useful approach in a variety of locales and for diverse interventions. Some examples are:

-

Summative evaluation of the Oxfam Novib’s Global Programme 2005-2008, a €22 million investment to support 38 grantees working on sustainable livelihoods and social and political participation. Documentation of more than 300 outcomes from 111 countries.

-

Retrospective 'Outcome Harvesting': Generating robust insights. Report on the evaluation experience of the BioNET global network to promote taxonomy for development. Identification and documentation of 200 emergent outcomes of BioNET.

-

World Bank Institute Cases in Outcome Harvesting. Ten pilot experiences identify new learning from multi-stakeholder projects to improve results. There is an average of 30 outcomes per pilot.

8 Strengths and limitations of Outcome Harvesting

The following are recognized strengths of Outcome Harvesting:

-

Overcomes the common failure to search for unintended outcomes of interventions;

-

Generates verifiable outcomes;

-

Uses a common-sense, accessible approach that engages informants quite easily;

-

Employs various data collection methods such as interviews and surveys (face-to-face, by telephone, by e-mail), workshops and document review;

-

Answers actionable questions with concrete evidence.

Limitations and challenges include:

-

Skill and time, as well as timeliness, are required to identify and formulate high-quality outcome descriptions;

-

Only those outcomes that informants are aware of, are captured;

-

Participation of those who influenced the outcomes is crucial;

-

Starting with the outcomes and working backwards represents a new way of thinking about change for some participants.

Resources

- What is Outcome Harvesting?

Ricardo Wilson-Grau (Sept 2014) explains the essence of the Outcome Harvesting approach in this brief video (< 3 minutes).

- Outcome Harvesting

This brief, written by Ricardo Wilson-Grau and Heather Britt, introduces the key concepts and approach used by Outcome Harvesting (published by the Ford Foundation in May 2012; revised in Nov 2013).

- OutcomeHarvesting.net

This website is a source of applications, events and resources to support the development of a community of practitioners of Outcome Harvesting. BetterEvaluation is one of three sister sites of OutcomeHarvesting.net.

- Outcome Harvesting Forum

Discussion of lessons being learned world-wide about how to adapt this alternative approach to monitoring and evaluation will be shared, challenged and advanced.

Expand to view all resources related to 'Outcome harvesting'

'Outcome harvesting' is referenced in:

Blog

Framework/Guide

- Communication for Development (C4D) :

Method